In this article, we will discuss why the existence of privacy-focused browsers doesn’t necessarily affect the effectiveness of fingerprint-based browser identification to prevent online fraud.

We start with a technical dive into how today’s anti-fingerprinting solutions work, focusing on uniformity and privacy-through-randomization techniques and their specific implementations. We list multiple examples from popular browsers, including one of the more popular privacy-focused browsers, Brave. We then elaborate on why device identification remains a valuable tool to prevent online fraud. Let’s dive right in.

Anti-fingerprinting

There are two common approaches when it comes to preventing browser fingerprinting. The more commonly implemented method makes all browser instances across all devices look as similar as possible. In theory, any fingerprinting should result in a single identifier or a very small number of different identifiers distributed across all devices, making the fingerprints useless.

This is typically achieved by making functional changes to web APIs known to be good sources of entropy. As a result, some APIs are completely disabled because most websites don’t rely on them. Others are revised to return a dummy value regardless of the actual real value. As you can imagine, these practices dramatically change users’ web experience for the worse.

However, some implementations hide the original functionality behind permission prompts. So the user can choose to let a website use a specific API in its original form, even though it might be used for fingerprinting (for example, the privacy.resistFingerprinting.autoDeclineNoUserInputCanvasPrompts advanced preference option in Firefox, which prevents websites from reading canvas data).

However, permission prompts are still not user-friendly, and most users do not understand the associated risks. Making a reasonable decision is, therefore, very hard. A good case in point is Chrome’s decision to handle some permission requests automatically without even notifying the user.

The second approach aims to make every browser instance as distinct as possible through randomization. As a result, every browser gets a random fingerprint that changes between websites and browsing sessions or between page refreshes. This additional randomness makes it impossible to use fingerprints for reliable identification. The Brave browser, a mainstream privacy-focused Chromium fork, was the first popular browser to implement privacy-through-randomization protections. One strongly voiced advantage of this approach is that sufficient randomization to prevent reliable fingerprinting can be done in a way that does not affect the web user experience. To better understand both approaches, let’s explore some examples.

(Learn more about what does (sometimes) and doesn't work for browser fingerprinting.)

Uniformity

Gecko’s (the browser engine behind Firefox and the Tor Browser) fingerprinting protection is a prominent example of the uniformity approach in the real world. The feature is controlled by the privacy.resistFingerprinting flag in the browser’s advanced preferences (about:config). At the time of writing, this feature is still considered experimental and disabled by default in Firefox because, as mentioned in the official documentation: “It is likely that it may degrade your Web experience.” Unlike the Tor Browser, which enables this feature for all security levels (the default being the “Standard” level).

Under the hood, this flag controls what values are returned from various web APIs. In some cases, these values are fixed across all platforms:

- The

prefers-color-schemeCSS media feature will always match “light.” - The

navigator.hardwareConcurrencyread-only property is set to 2. - The

navigator.maxTouchPointsread-only property is set to 0. - The

screen.colorDepthread-only property is set to 24. - The default time zone obtained by calling

window.Intl.DateTimeFormat()is always UTC.

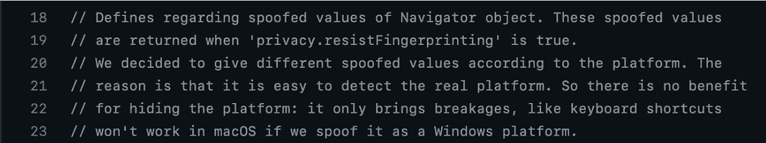

However, sometimes the spoofed, fixed values are platform-dependent. A comment in Gecko’s source code explains why this is the case:

As a result, calling navigator.platform will return either Win32, MacIntel, Linux AArch64, or Linux x86_64, still concealing the actual platform but placing users into different buckets nonetheless. Similarly navigator.userAgent, navigator.appName, navigator.appVersion and the Gecko-specific navigator.oscpu will return spoofed values.

Another good example of the uniformity approach to minimize fingerprint-able browser surface is the recent changes made to the deprecated navigator.plugins and navigator.mimeTypes features. The WHATWG HTML Standard was updated to reflect Flash deprecation and specified that browsers should always return a fixed list of supported plugins and mime types (depending on a new read-only navigator.pdfViewerEnabled property). Gecko and Chromium have already adopted the change.

Randomization

One common technique used for browser fingerprinting is based on the internals of the Canvas API. A developer needs to create a canvas, draw a specially crafted image on it, then extract the image data and hash it into a short identifier. Subtle differences in the video card, graphics driver versions, and system-level properties like installed fonts, usually result in the hash representing a simple, stable, high-entropy browser fingerprint.

The code can look like this:

const canvas = document.createElement('canvas')

const context = canvas.getContext('2d')

canvas.width = 122

canvas.height = 110

context.globalCompositeOperation = 'multiply'

for (const [color, x, y] of [['#f2f', 40, 40], ['#2ff', 80, 40], ['#ff2', 60, 80]]) {

context.fillStyle = color

context.beginPath()

context.arc(x, y, 40, 0, Math.PI * 2, true)

context.closePath()

context.fill()

}

context.fillStyle = '#f9c'

context.arc(60, 60, 60, 0, Math.PI * 2, true)

context.arc(60, 60, 20, 0, Math.PI * 2, true)

context.fill('evenodd')

const result = canvas.toDataURL()Please see this file from our open-source FingerprintJS library, for a production-ready example.

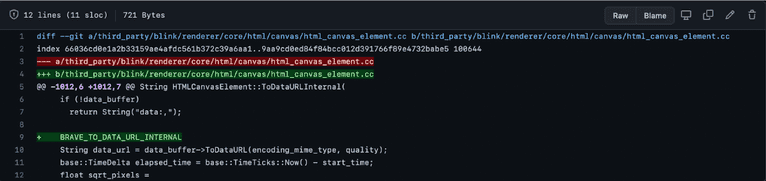

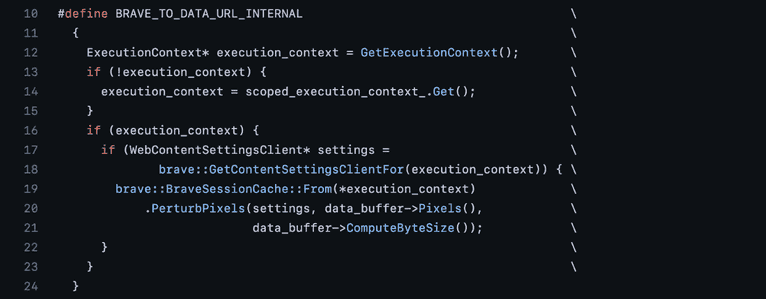

The last step, calling the HTMLCanvasElement.toDataURL() method, is when Brave’s anti-fingerprinting protections add randomization. The raw canvas data is passed through a method called PerturbPixels().

The method uses a per-eTLD+1 session key to change randomly selected bytes in the image data deterministically. This means that on different websites and whenever you restart the Brave browser, the data changes in a new way, meaning that the fingerprint based on this data changes, too. It is also worth calling out that the image data changes in an invisible way to humans, but because of how hash functions work, typical fingerprinting approaches yield different fingerprints.

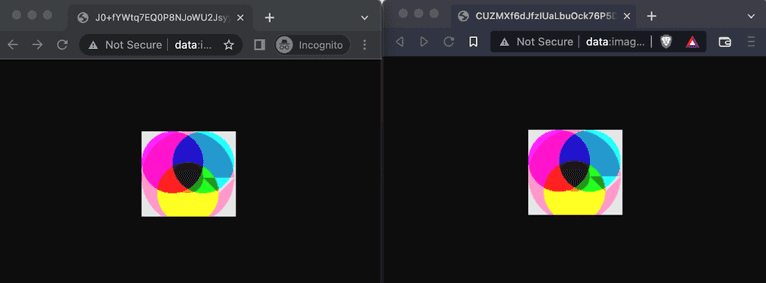

Here you can see how the image produced by the code above changes between Google Chrome and Brave:

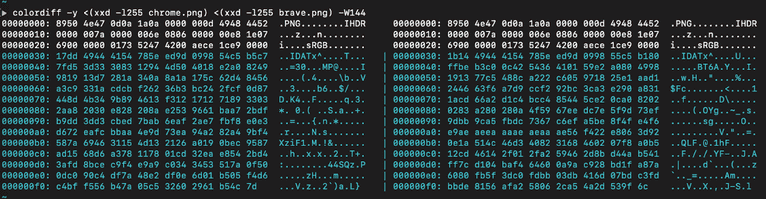

However, looking at the first 255 bytes of the underlying data, we can see the images are vastly different:

Needless to say, Brave does the same thing in three other methods that are used to serialize raw canvas data: CanvasRendering2dContext.getImageData, HTMLCanvasElement.toBlob, and OffscreenCanvas.convertToBlob.

Brave uses a similar approach for other sources of entropy, namely for the Web Audio APIs, when serializing data using the AnalyserNode and AudioBuffer interfaces and various WebGL APIs.

Randomization is considerably simpler for simple sources of entropy, such as navigator.hardwareConcurrency or the prefers-color-scheme CSS media feature. For hardware concurrency, depending on the fingerprinting protection mode, which can be either “default” or “max,” Brave chooses a number randomly between 2 and the true value or 8. The preferred color scheme is always reported as “light” if the protection mode is “max.”

Brave’s wiki pages show that the User-Agent, Plugins, and values returned by the Enumerate Devices APIs are also randomized. The Client Hints, Battery Status, Web Bluetooth APIs, and “HSTS fingerprinting” and “WebRTC IP leakage” are meant to be blocked instead.

Interestingly, however, this wiki page is currently not fully up-to-date as WebRTC has dedicated settings. Instead, the Client Hints JavaScript API’s getHighEntropyValues method returns accurate information, and the Battery Status API returns fixed values in all cases.

Prevention Challenges

As demonstrated in the examples above, using uniformity significantly reduces web experience. This can also be confirmed by looking at the relevant bug trackers, where users ask for options to disable anti-fingerprinting features, such as spoofing the timezone. As a result, browsers that implement this approach tend to have a limited user base and do not represent a mainstream alternative to browsers without custom anti-fingerprinting features. Using randomization has its challenges and, in many cases, still affects the web experience negatively, especially for entropy sources that return a simple value, like a number or a boolean flag. For this reason, most users still have to choose between using a “standard” protection or “maximum” protection.

More importantly, the algorithms for randomization are prone to several errors:

- Websites can detect artificial randomization by calling the affected APIs twice, finding anomalies in the randomized data, or simply assuming that values are randomized by identifying the browser. Websites can afterward either ignore these values or process them in a way that aids fingerprinting.

- The original entropy from the raw source data still exists, and implementations adding additional randomness to the underlying data might be reversible in practice.

- When other potentially indirect methods exist of learning about the raw source data, the original entropy can still be used without using one of the obvious ways to serialize the original data.

Both previously mentioned approaches, making all browser instances as similar as possible or as distinct as possible, fail to be effective unless they cover a significant number of potential entropy sources, which is quite hard to accomplish in real-world settings. And that proves to be very hard to do in real life.

Generating reliable fingerprints depends on the kind of traffic a website has and the effectiveness of anti-fingerprinting features. For example, if most users use a popular browser like Google Chrome, you need more entropy sources to differentiate and identify different Chrome instances reliably. On the other hand, browsers with a smaller user base are more easily fingerprint-able. In those cases, ignoring randomized entropy sources is also feasible.

wpoven.com and kinsta.com report that Brave has a market share of 0.05% for 2022. ctrl.blog mentions a 1.02% share amongst its readers in 2020. In addition, brave reports 50.2 million active monthly users in 2021.

For Firefox, statscounter reports a market share of 3.15% as of August 2022. Wikipedia mentions claims from different sources as of October 2021, varying from 2.18% to 4.4%. Firefox’s figures show around 200 million monthly active users.

Based on our internal information from August 2022, traffic originating from Brave on Desktop and Android accounts for 1.57% of all identification events. For Firefox, it’s 1.997%. Interestingly, Firefox traffic matches the values spoofed by the privacy.resistFingerprinting preference accounts for only 0.48% of all Firefox traffic we see. The Tor Browser accounts for 0.017% across all events.

Entropy sources are also not limited to just inherent browser characteristics. It’s important to acknowledge that system-level and network-level characteristics are just as effective. Additionally, fingerprinting can be supported via storing client-side identifiers too.

All this context is important to keep in mind when reasoning about the effectiveness of browser identification in the context of preventing online fraud.

You might have noticed that when exploring Brave’s implementation of the privacy-through-randomization technique earlier, we ignored the per-eTLD+1 aspect of it. It prevents third-party cross-site fingerprinting, which is especially important for web tracking and advertising companies. However, it does not prevent a site from fingerprinting its visitors in the same-site (or first-party) context (that’s what the per-session aspect of the randomization tries to do).

Preventing online fraud

Spamming comment sections, fake product reviews or coupons, cashback fraud, and abusing password reset and registration forms are all examples of online fraud that every big or small online service has to deal with inevitably. Even though all of these are very common, effective and scalable solutions prove to be very difficult to implement.

A simple solution often comes to mind is to put the affected functionality behind authentication. This is a good strategy as long as the functionality wasn’t explicitly designed for unauthenticated visitors. Moreover, with authentication in place, you have to deal with a new problem; automated account creation and verification. At this point, many services think about using a CAPTCHA, whether it is to stop the automated account creation or the original form of abuse.

Inevitably, CAPTCHAs will lead to a worse user experience and reduce conversion rates. However, more often than not, the abuse returns through other means. For example, when native mobile APIs expose the same functionality, CAPTCHAs won’t help, as their native apps support is essentially non-existent.

Online services need reliable web browsers and native mobile device identification in these situations. In our experience, when done right, browser fingerprinting works wonders to prevent online fraud. Furthermore, because it happens in the background, it does not introduce additional friction unless a user is deemed fraudulent. To learn more about specific examples, you can read through our case studies, use case guides, or contact us and get hands-on guidance on incorporating Fingerprint Pro’s high accuracy identification API into your fraud prevention stack.